Licensed to thrill: Gabby Malpas has a sting in her tail

The New Zealand-born painter and ceramicist has built a thriving art business, creating objects of beauty from her life experience.

A conversation with painter and ceramicist Gabby Malpas is like taking a bracing holiday from cliché. It is enervating and she has little time for fluff. While other artists may breezily claim to be inspired by beauty, light or even the thrumming sound of butterfly wings, Gabby’s motivations are far more visceral.

A self-supporting ceramicist and painter, Gabby, 58, is gutsy. There is an undertow of fury, roiling within her, as the adopted Chinese daughter of a white family, raised in a society intolerant of difference.

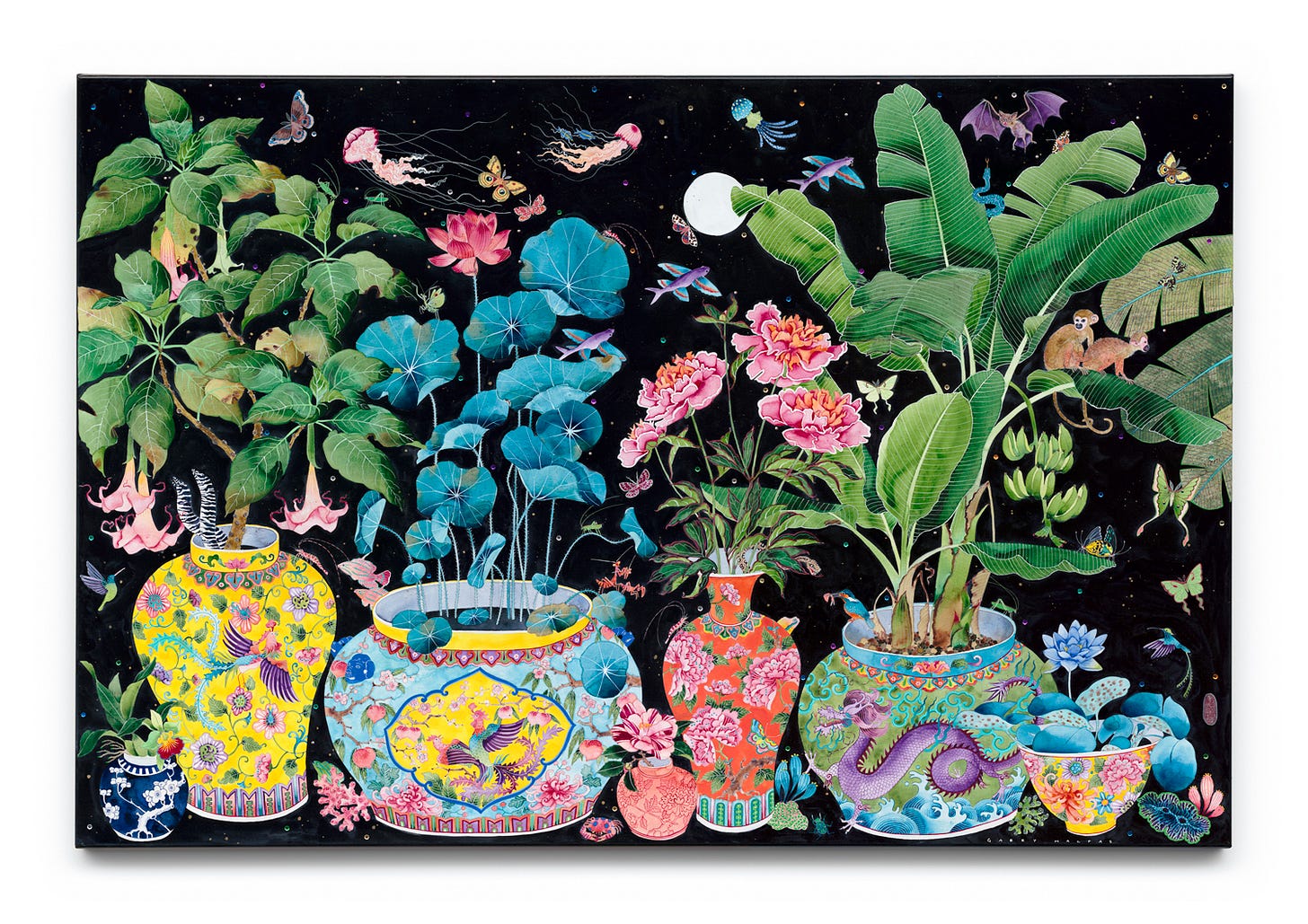

But observing her from a distance, you could be utterly oblivious to the turmoil, beguiled by her joyful Chinese-inspired ink and watercolours and glistening glazed bowls. Because she’s clever like that.

Gabby says the only thing less acceptable in our society than an angry woman is a brown angry woman. She’s clearly passionate, but she also laughs a lot and is raucous. She’s mindful not to scare the horses.

“I’m doubly careful because I’ve got a business to run. We all censor ourselves,” she says.

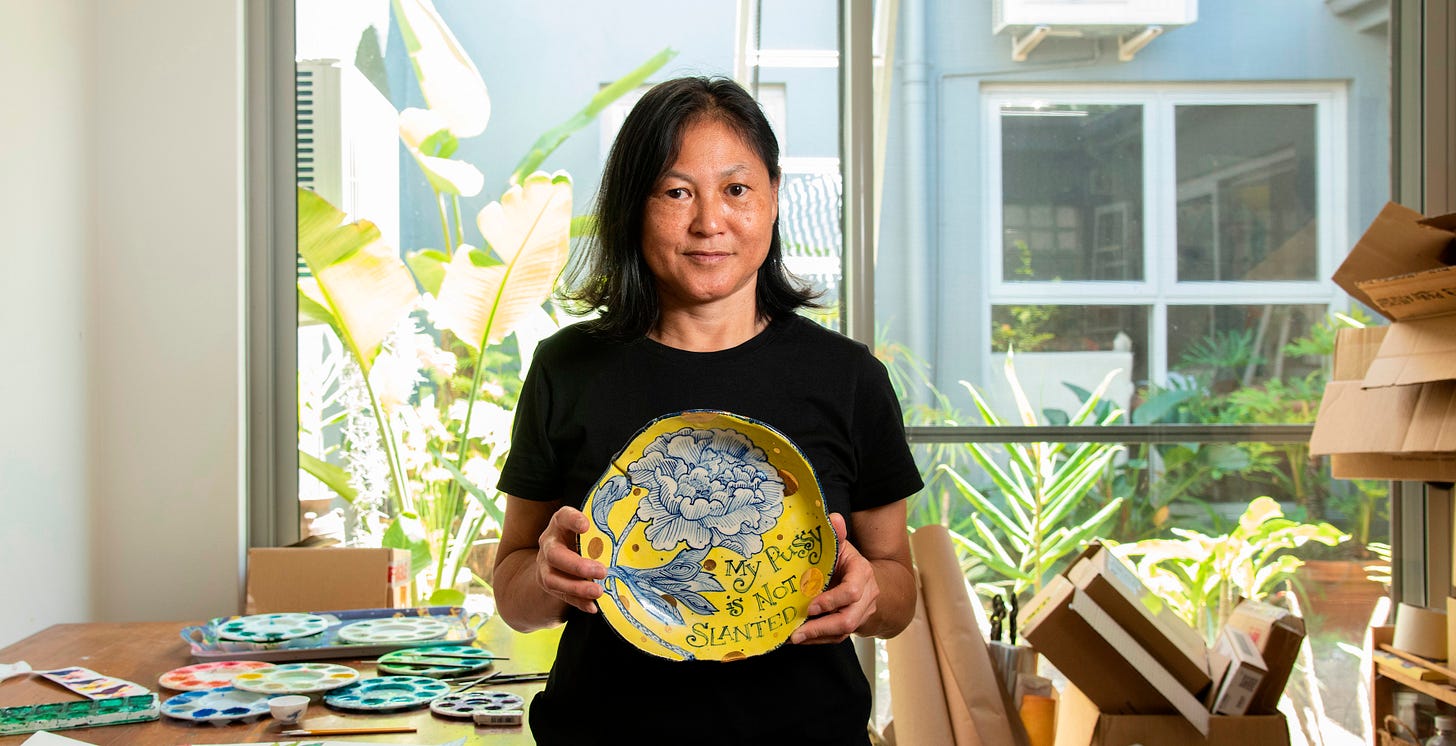

So, if you want to see what she is really thinking, then you will have to look beyond the calm beauty of her more commercial works. Turn instead to the pieces she creates for her own amusement – where she is practising “quiet activism”.

In her interview with the Business Of Art, Gabby discusses her history and activism, her practice, and the intricacies of art licensing.

Trans-racial: Crossing boundaries can be complicated

As an adoptee of Chinese parentage, born and raised in Auckland, Gabby has had to contend with racism all her life. In the 1960s and 1970s, Asian features were not a common sight in New Zealand and people felt relatively uninhibited about staring and taunting.

Lately, she has noted significant cultural changes and, as a Kiwi of a certain age, acknowledges the huge privilege she was given via a free tertiary education at art school.

In more recent times, Gabby’s European name has become another complication, prompting assumptions from people who could not see her face. She has, for instance, lost count of the times she has had to defend herself online from charges of cultural appropriation or being told she is not a “true Chinese” by gatekeepers.

When it comes to her origin story, Gabby says her Catholic adoptive parents, Christians in the oldest sense, just didn’t know how to say no. When their church asked them to take on a newborn Gabby, she was enfolded into their brood as the youngest of 10 children. Before her arrival, there had also been a number of foster siblings.

Her birth mother, a single woman, had travelled to New Zealand to stay at a Catholic Care home for the delivery and was the daughter of educated professionals – although Gabby wasn’t to learn about their social status until she met her birth mother for the first time, 20 years ago.

Up until then, it had been presumed by the adults who dealt with the adoption process that her mother was poor, uneducated and, possibly, a prostitute. Her adoption papers, which she hasn’t seen, apparently stated her mother was an artist.

“My bio grandparents were university-educated teachers and professors. They left China during the Cultural Revolution because they were Catholic. Whereas, my adoptive parents left school after the 11 plus and didn’t have higher education – which was usual for folks of their background.”

Gabby was encouraged to pursue an art career and studied ceramics at the Otago Polytechnic School of Fine Art. She left for London, forging a career in digital project management for 14 years, while showing her paintings in galleries.

“I left New Zealand in 1988 because, at 23, I felt I would never be accepted as a Kiwi, even though I was born there,” she says. “Things have definitely changed, but that hurt.”

She migrated to Sydney 21 years ago: “I’ve experienced racism in the UK and Australia, too, though it is becoming less acceptable” she says, adding “There’s still a lot of work to be done. Let’s not rose tint it.”

One of the pernicious impacts of being “implanted” as a baby into a different culture is that racism can be internalised. Children, naturally, want to belong.

“I wouldn’t admit that I wasn’t white until I was probably 30. Now, that says a lot. That’s quite a shocking statement, but it says a lot about how I saw myself in the society I grew up in.”

(Dragon animation available from Sugar Glider Digital)

Engaging with her past – quiet activism

Everything changed when Gabby finally made contact with her birth mother in 2004.

“That huge cultural door opened. I felt there was almost permission – ‘You are Chinese now. You are one of us’.”

The result in her art practice was what she has called “Chinoiserie reimagined”. She finally accepted and integrated her genetic heritage and embarked on a journey of self-discovery, exploring the Chinese art and motifs that fascinate her, but on her own terms as a “cultural outsider”. This “otherness” is often experienced by bi-racial people and 2nd+ generation immigrants who feel disconnected to their heritage.

It seems particularly neat that she is inspired by Chinoiserie, which is a romanticised depiction of Chinese art for Western eyes. Gabby herself could be seen as a human version of cultural boundary spanning.

Over the years, and as her art business gained prominence, Gabby has walked a tightrope in balancing her passion for social justice with her concerns about alienating her audience. “I’m now courting and making activism work, but a lot of my audience is your standard Nanna who wants something nice for Mothers Day. I’m thankful I wasn’t on social media when I was really young and angry and spouting all sorts of shit – I’ve toned it down a little bit.

“But, equally, I’ve got to be brave enough to say, okay, look, I’m prepared to lose a few followers over that.

“Not all of my art is activism. I just do some of it because I like it, I’m working to a brief, or it amuses me.

“Activism art for me is not to shock, not to outrage. I engage with what I call quiet activism,” she says, pointing to her first show about her own life at the now-closed Platform 72 in Chippendale, Sydney in 2004.

The show was called “Where are you from?” and Gabby contributed some blue and white porcelain pieces in a series provocatively titled “Ching Chong”.

“It’s gentle, but it can also be as divisive as you like. It does have a sting in its tail. It is the cheekiest way I could say ‘Fuck you’.

“So, it’s gently prodding and gently raising awareness. We’ve got to draw people in, and they’ve got to want to look. That’s where the prettiness comes in: the beauty, the quirky, the crazy, and the good skills.

“And you’ve got to have an audience to do that, which is why you see me posting like a demon with good content.”

What her week looks like

She works 7 days a week

This includes 2-3 days painting at home.

Two days a week, she is at the Clay Sydney studio in Marrickville.

The rest of the week is for administration, submissions, photography and posting to social media.

She spends about one hour a day on social media.

A freelancer in India provides services such as deep etching and animations.

She makes time for gallery openings to support other artists.

The jump-off point - Switching to full-time art

Gabby waited until her art turnover matched her freelance turnover, and then quit her last freelance job in 2019 to become a full-time artist at 53.

Turnover: the amount of money a business takes in a particular period. Not to be confused with profit.

“It took me at least 10 years to start applying what I had learned in business to my practice. I didn’t feel confident or feel I was good enough.”

Gabby’s website sells various products, including original paintings, ceramics, silk scarves, stickers, cut-out dolls, prints, and various stationery items.

The shape of her business

Average turnover of around $120,000 per year

Licensing contributes about 30%

Private commissions around 20%

2D artworks and Ceramics in galleries 40%

Talks and workshop fees 5-10%

A primer on licensing - is it right for you?

If you have ever walked into a department store and admired the Maxwell & Williams tea sets, you will have seen some of Gabby’s work. Licensing her artwork for commercial use now makes up a significant part of Gabby’s practice, driven in part by her social media presence.

Licensing involves granting a company the right to reproduce your artwork on products in exchange for a fee and/or royalties.

“People look me up, like my work, and approach me and we start the dance. Because of my background in business, I can negotiate and draw up a contract to tell them what I’m willing to do,” she says.

Gabby has some tips for others interested in creating another income stream.

First, you have to consider whether your work is suitable. Some artists may get one-off deals for a book cover or clothing line, but it will not necessarily turn into a “regular earner”.

To make it part of your business plan, you need a library of suitable work in a high-quality format.

Gabby has more than 2,000 scans of her work and owns a professional-quality scanner for smaller pieces. Larger artworks go to a specialist with large format equipment – creating images big enough to grace the sails of the Sydney Opera House.

For the past 10 years, she has been paying a freelancer in India to stitch and manipulate her images into usable images for clients.

She also ensures she has variety. Commercial clients want a selection to choose from.

“So, you don’t just do one picture of an apple. You do four, one for each season, and then you’ll do another couple with cores or blossoms. It forms a collection,” she says.

Gabby has a rate card, but adjusts it depending on the job and the client. “It’s like selling a painting. You have to know how much the market will bear.” Prices can range from $250 (as a favour) to $2000 for an image.

“It’s my choice. I’ve taken the power back about how much I charge and it’s not always about the money.”

If a prestige client uses an artist’s image, it can be a “career-builder”, she says. “But what that means is, usually, they then own that image in perpetuity.”

While being paid in one large lump sum is ideal, her best profits so far have come from royalties. In her highest-earning years, she has raked in around $20,000 a quarter (three months).

“There was a couple of years where I made damn good coin.

“But that can go up or down. That is possibly the hardest part of licensing; you cannot predict sales.”

The Silk Road range that Maxwell &Williams produced five years ago evolved from an amalgamation of motifs from about five paintings. She has a 10-year working relationship with the company.

Five things you should think about

1. Right direction. Do you want your work to be used commercially? Does that align with your art goals?

2. Suitability. Are your images clean enough to be put into repeating patterns? Are they relevant?

3. Quality. Are the images of sufficient quality?

4. Quantity. Do you have enough useable images for a healthy selection?

5. Differentiation. What is your point of difference and are the images recognisably yours?

6. Record-keeping. You will need to keep excellent records of your contracts to ensure you don’t re-sell something that has already been licensed to another client.

A copyright licence is available from the Arts Law Centre of Australia for $200.

Gabby’s licencing deals:

Minus Art wall prints

Blue Island Press stationery

Maxwell & Williams homewares

OneKingsLane art prints

Groupe Editor stationery

Kate Dickerson Needlepoint and tapestry kits

Gabby’s work can be seen at Grainger Gallery in Canberra, the Manyung Gallery Group in Melbourne, Gallery NWC in Katoomba, the Australian Design Centre in Darlinghurst, Sydney, the Thienny Lee Gallery in Edgecliff, and Brenda Colahan Fine Art in Putney, Sydney. She also works with consultancy Art Pharmacy on corporate commissions.

The Business of Art is written by former Australian Financial Review journalist and now full-time artist Fiona Smith as a pro bono project to improve business literacy in the art community and help artists work smarter and more profitably. Please support the project by subscribing and forwarding the newsletter to people who may find it interesting.

Thank you for the Gabby Malpas writing. Interesting to read about a professional’s long term art and business practices